The use of ionizing radiation in healthcare has experienced steady growth over the past decades, both in terms of the number of diagnostic examinations and, particularly, in imaging-guided interventional procedures. The expansion of interventional radiology, interventional cardiology, and hybrid procedures has led to a significant increase in occupational exposure for healthcare professionals, especially in settings where fluoroscopy is used for prolonged or repeated periods. In this context, radiation protection can no longer be considered an accessory or purely individual measure, but a structural component of environment design and the organization of clinical workflows. The traditional approach to radiation protection, historically based on the use of personal protective equipment, has over time shown clear limitations, particularly in terms of ergonomics and operational sustainability. The increase in the average duration of procedures and frequency of exposure has made a comprehensive rethinking of protection strategies necessary, shifting the focus toward integrated and collective solutions.

Training by RIMSA

Radiology Protection System

X-ray Radiation Protection Systems

Technical Evolution, Design Criteria, and European Regulatory Framework

Evolution of Radiological Exposure in Healthcare

1

From Personal Protection to Collective Protection

Personal protective equipment (PPE), such as lead aprons, thyroid collars, and shielding glasses, still represents an essential element of radiation protection. However, relying solely on PPE has well-documented limitations. The high weight of leaded PPE is associated with an increased incidence of musculoskeletal disorders among operators, particularly affecting the spine and joints. Furthermore, the protection provided by PPE is limited to the covered body areas and heavily depends on correct donning and maintaining proper positioning during procedures. These limitations have driven a gradual shift toward collective protection systems, designed to reduce exposure at the source before the radiation reaches the operator. In this context, mobile radiological protection systems play a central role, allowing shielding to be integrated directly into the work environment without significantly interfering with clinical operations.

2

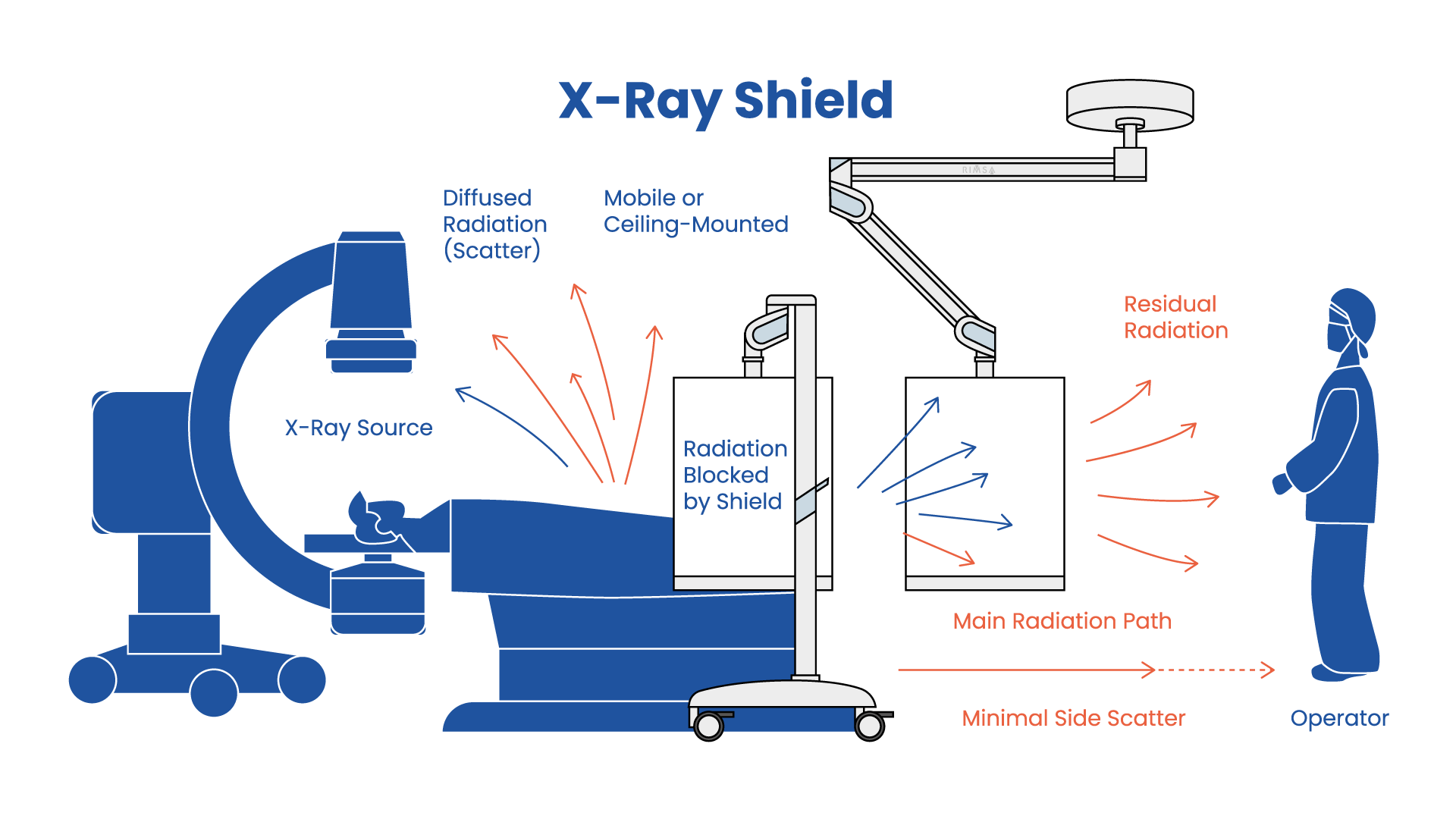

Mobile Radiological Protection Systems: Principles and Functions

Mobile radiological protection systems are designed to create a shielding barrier between the radiation source and the operator, while maintaining visibility and freedom of movement. Unlike fixed shields, these devices offer flexible positioning and adaptability to different room layouts, making them particularly suitable for multifunctional environments such as hybrid rooms, interventional radiology suites, and operating rooms with integrated imaging. From a technical perspective, the effectiveness of a mobile system depends on a combination of factors: shielding material, lead-equivalent thickness, barrier geometry, height, and structural stability. The design must consider not only the attenuation of primary and scattered radiation but also the operational procedures and positions assumed by operators during the procedure.

3

Shielding Materials: Acrylic, Glass, and Leaded Glass

X-ray radioprotective screens can be manufactured from various materials, selected based on the level of required protection, transparency, mechanical strength, and ease of handling. Shielding acrylic, optionally enriched with lead or other high atomic number elements, offers lightweight construction and ease of maneuverability, making it suitable for contexts where basic protection and frequent repositioning of the device are needed. However, the durability and optical quality of acrylic may be lower compared to other solutions, especially over the long term. Glass represents an alternative with better mechanical strength and visual quality. Its shielding capacity remains limited unless combined with high-attenuation materials, but it is suitable for applications where robustness and optical quality are priorities. Leaded glass provides the highest levels of radiological protection, combining excellent transparency, durability, and strength. Its greater mass suggests use in high-exposure contexts and for mobile devices designed for stable positioning during prolonged procedures, such as suspended screens or those integrated into the operating room.

Lead Equivalence and Protection Levels

The reference parameter for the shielding capability of a radiological protection system is lead equivalence (mm Pb), which indicates the thickness of lead required to provide attenuation of ionizing radiation equivalent to that of the material considered at a given energy. In clinical settings, the most commonly used values for mobile or suspended shields range from 0.5 mm Pb to 1.0 mm Pb, while higher values are reserved for specific situations.

The choice of protection level must be based on a radiological risk assessment specific to the environment and the procedures performed, taking into account factors such as the type of equipment, X-ray beam energy, distance from the source, duration of exposure, and room geometry. In this sense, lead equivalence should be interpreted as a design parameter, not as an absolute value valid in every context. Measurement of lead equivalence must comply with the requirements of IEC 61331-1:2014.

Why the Attenuation Law is Important in Radiation Protection

The reduction in intensity of an X-ray beam as it passes through a shielding material is described by the exponential attenuation law:

I(x)=I0*e−μx

- I0= initial radiation intensity

- I(x)= intensity after passing through a thickness

- μ= linear attenuation coefficient of the material (depends on the type of material and radiation energy)

- x= thickness of the medium traversed

- e= Euler’s number

This relationship is fundamental because it shows that radiation protection does not increase linearly with material thickness: each increase in shielding results in a progressive reduction in exposure according to an exponential law. Understanding this principle makes it possible to design radiological protection solutions that are effective and proportionate to the risk, avoiding both insufficient shielding—which unnecessarily exposes operators and patients—and oversizing, which increases weight, bulk, and complexity without real benefits. The formula also provides the theoretical basis for applied concepts such as lead equivalence, the half-value layer (HVL, the thickness that halves the intensity), and the tenth-value layer (TVL, the thickness that reduces the intensity to one tenth), which are used in the practical evaluation of shielding. In this sense, the attenuation law represents the direct link between radiation physics and the concrete design of safety in healthcare environments.

4

Integration of radiation protection systems into the layout and suspended systems of the room

The effectiveness of X-ray radiation protection systems does not depend solely on the characteristics of the shielding material or on the lead equivalence value, but decisively on their integration into the functional room layout and existing support systems. In highly technology-dense environments such as operating rooms with integrated imaging, hybrid rooms, and interventional radiology suites, radiological shielding introduces loads, volumes, and movement constraints that must be addressed at the design stage rather than treated as a subsequent add-on. In this context, radiation protection should be considered an integral part of the room’s technological infrastructure, on a par with surgical lights, monitors, imaging systems, and other suspended devices. Radioprotective screens, made of shielding acrylic, glass, or leaded glass, are not merely passive elements but devices that must be precisely positioned relative to the radiation source and the operator’s working posture. The ability to create shielding with customized geometries and dimensions allows protection to be adapted to the actual exposure field, improving effectiveness against scattered radiation while reducing unnecessary bulk. From a hospital engineering perspective, integrating shielding into articulated arm structures, single or multiple, represents a solution consistent with space optimization and operational safety principles. Ceiling- or wall-mounted suspended systems support the weight of the screen, ensuring balance and stability while providing a wide range of positioning freedom. The option to configure systems with two independent screens meets the needs of procedures in which multiple operators are simultaneously exposed to scattered radiation, enabling targeted protection without interfering with the visual field or clinical gestures. Another key design element is the integration of radiological shielding within multifunction suspended systems, shared with other medical devices such as surgical lights, monitors, cameras, or accessories, which helps reduce floor clutter, simplify workflow management, and improve the overall order of the working environment. In complex rooms where multiple devices and operators coexist, minimizing physical interference between equipment is critical for safety and operational efficiency. Mobile solutions on wheels represent a complementary expression of this integrated approach and are particularly suitable for multifunctional environments, rooms where structural modifications are not feasible, or settings in which room configurations frequently change; even in these cases, the design of the support system—stability, maneuverability, the ability to mount one or more screens, and compatibility with other devices in the room—directly influences the actual use of protection during procedures. Taken together, these solutions show that the transition from personal protection to collective radiological protection requires an integrated engineering approach in which shielding, support systems, and spatial organization are considered parts of a single system, allowing radiation protection to become a naturally incorporated element of the clinical gesture, always available and correctly positioned, rather than an operational constraint perceived as external or ancillary.

5

The propagation of X-rays in a room: is it predictable?

Yes, the propagation of X-rays in a clinical room is predictable within well-known margins, and it is precisely on this predictability that the design of radiological shielding is based. In medical procedures, the main contributor to operator exposure is not the primary beam, which is directed toward the patient and highly collimated, but the scatter radiation generated by the interaction of X-rays with the patient’s body and the table. This scattered radiation predominantly propagates::

- from the patient,

- with maximum intensity in directions close to the plane of the beam,

- with a spatial distribution that depends on the source geometry, the kVp, and the operator’s position.

Numerous dosimetric studies show that the operator is significantly exposed only in specific regions of space, typically between the source, the patient, and the working position. This makes it possible to intercept most of the dose with properly positioned shielding without having to fully enclose the space.

Why is a radiation shielding screen adequate (even if it does not completely enclose the room)?

A mobile or suspended radioprotective screen is effective because::

- it intercepts the primary scattered radiation, which represents the dominant portion of the dose to the operator;

- it is positioned between the patient (scatter source) and the operator, i.e., along the most probable path of the scattered photons;

- it drastically reduces the intensity of the radiation field before it reaches the operator’s body, as described by the attenuation law.

It is not necessary to shield “all around,” because the dose is not isotropic: it decreases rapidly with distance and with the angle relative to the main emission plane. From a design perspective, effective protection is directional, not volumetric.

Can radiation come from the side or from behind?

In theory, yes, but to a very limited extent. The scattered radiation that reaches the operator laterally or from behind::

- has already undergone multiple interactions (multiple scatter),

- has lower energy,

- contributes only marginally to the overall dose compared to the direct scatter intercepted by the screen.

For this reason, regulations and good practice do not require a “fully shielded capsule,” but a properly positioned collective protection, integrated with:

- distance from the source,

- optimization of exposure parameters,

- residual use of PPE where necessary

Why position matters more than thickness

A shield with an adequate lead equivalence but poorly positioned provides limited protection.

A correctly positioned shield, even with moderate thicknesses (e.g. 0.5–1.0 mm Pb), can reduce the operator’s dose by orders of magnitude, as it intercepts the radiation field before it disperses into the surrounding space.

For this reason, the following systems:

- mobile systems on floor stands,

- ceiling-suspended systems with articulated arms,

are preferred as they allow the barrier to remain consistently aligned with the source of scattered radiation, adapting to the operator’s actual position.

6

Towards safer and more sustainable workplaces

The transition from personal protection to collective and mobile radiological protection systems reflects a broader shift in how safety is approached in healthcare. Radiation protection becomes an integral part of room design and process organization, helping to create safer, more ergonomic, and sustainable working environments.